To watch Deep Dive MH370 on YouTube, click the image above. To listen to the audio version on Apple Music, Spotify, or Amazon Music, click here.

For a concise, easy-to-read overview of the material in this podcast I recommend my 2019 book The Taking of MH370, available on Amazon.

Thanks to our Episode 20 sponsor, Finnished MKE. More information here: https://www.instagram.com/finnished_mke/

Last episode we talked about the surge of MH370 debris that started turning up in the western Indian Ocean in early 2016, and how search officials were optimistic that all this new data would help them understand where the plane went down. We focussed on drift modeling, and how the timing and location of the finds could have helped pin down the location of the crash through a process called reverse drift modeling. But to their surprise, Australian scientists couldn’t get their drift models to explain how the flaperon went all the way from the 7th arc to La Réunion Island in just 16 months. Then they obtained a real flaperon from their American counterparts, cut it down to match the damage found on the real MH370 flaperon, and put it in the ocean. They found that it floated high in the water, and the wind pushed it so effectively that when they plugged the new data into their models they found the flaperon now indeed was able to reach La Réunion on time.

Today, we’re talking about other clues that the authorities were able to derive from the collected debris, namely the marine fauna found living on them. And to help us understand, we’re bringing in Jim Campbell, the world’s leading expert in marine invertebrates.

Jim spent years researching how debris that was washed into the sea during the 2011 tsunami in Japan collected organisms as it drifted across the Pacific before coming ashore in the western United States and Canada. By examining the organisms growing on each piece Jim was able to figure out the path the piece had taken. He coined the term “bioforensics” to describe this kind of detective work.

As you’ll recall from last episode, one of the great puzzles that search officials had to grapple with in running their drift models was, how did the flaperon float? From the get-go, French investigators noticed that the piece seemed to have floated fully submerged because it was totally covered by barnacles.

Let’s do a quick review of the basics. Lepas barnacles attach themselves to floating objects below the waterline. They don’t grow on the part above the waterline, where they would dry out and die.

When the flaperon washed ashore on La Réunion, it was hard for investigators to figure out where the waterline was, because it was covered with Lepas all over, including on the trailing edge:

Yet when the French put the real flaperon in a test tank, and the Australians put a replica flaperon in the ocean, both floated with the trailing edge sticking high out of the water:

In the first part of my interview with Jim, I ask him how he can resolve this discrepency. It’s simple, he says. The piece didn’t float with the trailing edge sticking up out of the water. ATSB drift modeling be damned, barnacles don’t grow in the air, so the flaperon must have floated so low in the water that it was at least awash. If it was as buoyant as the float tests suggest, something must have been holding it down. Maybe it was attached to another piece of the airplane, or maybe it got tangled in a heavy fishing net, but somehow something must have been holding it down. “Lepas don’t lie,” he says.

Next I asked him about the organisms found growing on the other pieces of debris. After Australian authorities collected these pieces they gave them to marine biologists to identify the createres living on them. Hopefully, they would be able to use bioforensics to narrow down what part of the ocean the plane had crashed in. Yet it was not to be, because what the scientists found was quite odd. None of the pieces had any marine life that matched what you’d expect for an object that had been floating for a year and a half from the 7th arc on the other side of the Indian Ocean. Especially puzzling was what they found living on the piece that Blain Alan Gibson found, which was called No Step. Most of the things they found don’t live in the open ocean, they live close to shore. And the things that they found that do live in the open ocean were all really young, like less than two months old. The only things that were even moderately old, like 8 months old, were animals that only live close to shore.

One was called Petaloconchus renisectus, a kind of sea snail.

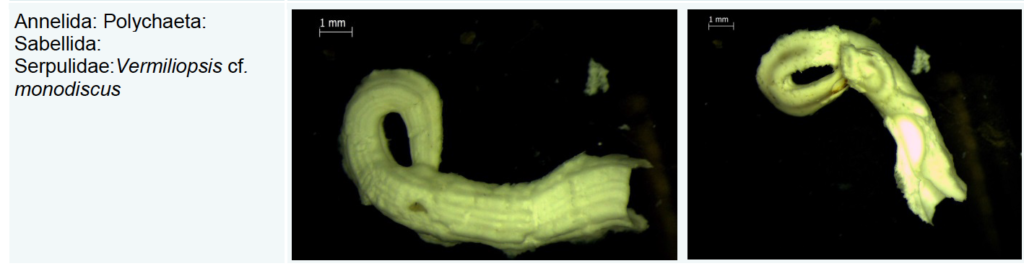

The other was a tube worm of the serpulid family called Vermiliopsis.

So how did they get on this piece that was floating across the middle of the Indian Ocean?

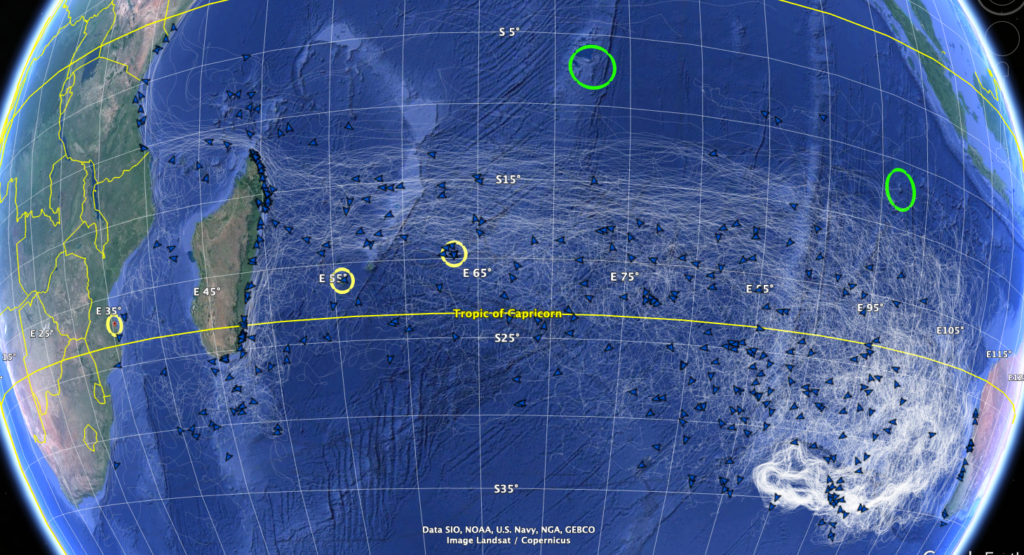

There’s no mystery, Jim says: Eight months before coming ashore, the flaperon must have drifted close to a shoreline. But where? The map below shows the Indian Ocean where the flaperon is presumed to have drifted. The white lines show the paths of individual bits of simulated debris. The whiteness is densest in the southeastern part of the ocean, where the paths all begin. As you can see, a few of these paths pass near Cocos Islands, the green circle on the right, but most pass far to the south. Fewer still drift past Diego Garcia, the green circle on the left. Vilanculos, where No Step was found, is the yellow circle on the far left. It’s possible that this kind of scenario could have occurred. But it raises the question: how come no species that live in the open ocean were found? And if pieces floated close to the Cocos Islands, why did no debris come ashore there?

Another problem we touched on last time was the strange Mossel Bay piece, aka Roy, that washed ashore at the southern tip of South Africa several months after the flaperon was discovered.

Based on my own rough-and-ready visual analysis, it seems like the barnacles are smaller than the ones on the flaperon — but since they’ve been at sea longer, so should be older and bigger. This is another puzzle.

Likewise, the biggest barnacle on the piece found on Rodrigues was only 20 mm which means it was probably no older than 105 days.

Indeed, it looks like all the pieces that washed ashore started growing when the piece was already halfway across the ocean. How to explain this? One idea is that there used to be older ones but they all got eaten or scraped off somehow, but scientists who study Lepas have told me that that doesn’t really happen out in the open ocean.

The enigmatic, self-contradicting nature of the MH370 debris is so different from the clarity provided by the tsunami debris, where you can clearly see the progress of each object’s drift reflected in the sea creatures that got picked up at each stage of the journey.

It all seems pretty baffling — unless you put in the context of everything else we know about the mystery of MH370, which is that if you take everything at face value then paradoxes abound.

PS:

A viewer asked in the comments to the YouTube page for this episode “Can the gooseneck barnacles survive if the surface on which they are attached gets splashed frequently with ocean water, even if the substrate is not 100% submerged under the surface?”

The answer is that if a floating surface is frequently awash with ocean water it seems that some meager Lepas populations can survive. A few years ago a marine researcher shared with me some images of a capsized boat that was recovered after drifting for some time.

The bottom and sides were super heavily encrusted with marine organisms:

The top had far fewer — but not none, except maybe in the very middle:

It’s worth noting, I think, that the Lepas growing on the trailing edge of the flaperon aren’t stragglers struggling to survive in the harsh barnacle-unfriendly region near the waterline, but one of the denser and robust populations on the whole object. Which I interpret to mean that they they were consistently underwater.

Hi Jeff:

How about a quick video on the new Amelia Earhart information? Seems promising.

The Amelia Earhart disappearance is certainly the MH370 of the 20th century… might not be a bad idea. I’m not so optimistic about this new sonar image, though. There have been just too many claims in that case made on dubious evidence.

Hi Jeff. Congrats on the ongoing podcast series – you’re really covering a huge scope of information.

I’d appreciate if when you have a moment you could share how some of the specifics regarding how you’re recording and editing the podcasts? And are you writing each episode out fully in advance? It’d be great to get a behind the scenes view of how you and Andy actually put it together.

Jeff, I could listen to you talk all day! You are brilliant. I absolutely love this fascinating podcast, and anxiously look forward to it every week! Thanks to you and Andy for working so diligently on this. Can’t wait til next weeks’s episode!

Thanks Kelly! So glad you’re enjoying the show.

@DG, Thanks so much! Each week I write up an outline that’s pretty much a short article on the topic, then share it with Andy. He’s the MC so he’ll use it as his guide to the conversation and will read stats and quotes for it, and cue me up to basically talk off the top of my head about what I’ve just written. Then when we’re done Andy does the editing and posts it on YouTube and the podcast platforms while I write up the show notes for the web site. It’s a lot of work but I think we’ve gotten into a rhythm. It helps that I’ve got a pretty big larder of stuff to draw from.

Just for a thought:

1.The day MH370 disappeared , there was a bag (earthquake) west of Maldives..

2.Fire suppression bottle of similar flight washed on Maldives beach

3. Maldives ( Kudahuvadhoo) witnessed a flight in the morning hours

4. The simulator of Captain taken immediately to US

5. The calculated location for search ( one of the difficult environments and unchartered areas)

6. Unknown buoyant devices seen by Fisherman in Maldives

7. Identical MH15 explosion above Ukraine

8. Inmarsat staff sudden death

9. Blaine Gibson come and go !

Jeff – just saw this TV news report of Ocean Infinity offering to do another search?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mu9NMI4QH10

and one of the stories is here:

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/ocean-infinity-malaysia-airlines-missing-flight-mh370-b2506995.html

Might you have heard what “new evidence” OI thinks they have?

P.S. sent you an email

Hi Jeff,

Thanks again for your unflagging doggedness and journalistic integrity on the disappearance of MH370. For 10 years! Your work remains to this day the only credible theory to me; this article is a perfect example of why that is so.

Nevertheless, after reading an article on a new theory on DailyMail, I realized I had momentarily forgotten your website name, so went to Wikipedia to refresh myself on your name. I was shocked to see that your theory has basically been scrubbed from those Wiki articles (with one rather dismissive exception)! Which probably means- your theory is correct . And various entities therefore want to bury it.

So keep up the good fight! It matters.

Assuming that research proves that the lepas on the pieces of the plane are too young to have been there since the time of the crash that means that someone planted these pieces in order to deceive.

What would be the point?

If, as some believe, the wing piece is from the downed 777 in Ukraine, why go to so much effort to make it seem like it was from mh370?

Hey Kay, Yes, I agree that the young age of the Lepas (as well as other noted discrepencies) suggest that the pieces were planted. The point would be to reinforce search official’s impression that the plane really had go into the ocean, which by March 2015 had started to look a little shaky, as it was entirely premised on a handful of mysterious satellite signals and it was becoming clear that these could have been tampered with. As to the suggestion that the pieces came from MH17, that’s mistaken. We know from internal serial numbers that the flaperon, for instance, came from MH370.

Hey Blair, Thanks so much, I really appreciate your support. That sucks about Wikipedia, there are people who are inexplicably (in my view) hostile to the spoof theory. It’s a funny world.

Thanks, Dan. I’ll check it out.

@Shareef, Hmmm, what do you think it all means?